Copy-on-Write in Agentic Systems

Copy-on-Write (CoW) enables database-level isolation for agentic workflows, so users can review and approve agent outputs before they permanently affect production data. Agent changes are written to a separate 'changes' table, but appear merged with 'base' (production) data in the agent's view. At the end of a session, the user can selectively commit agent changes to the main database. This article introduces a CoW implementation to a SQL database, as well as a worked example of CoW in a farm Inventory Management System.

An accompanying demo for this article can be found at: https://agent-cow.com/ (GitHub)

AI agents are increasingly being deployed in software contexts to plan and execute sequences of actions on users' behalf. More frequent agent use, on potentially sensitive production data, means the stakes of misalignment grow proportionally higher.

Alignment is an open problem in AI safety, and misalignment during agent execution may not always be obvious. At best, a misaligned agent is annoying (i.e. if the agent does something other than what the user wants it to do) and at worst, dangerous (i.e. leading to sensitive data loss, tool misuse, and other harms).

Rather than tackling the alignment problem directly, this article focuses on minimizing potential harm a misaligned agent can cause. Specifically, we will discuss how Copy-on-Write (CoW), a database isolation mechanism, can mitigate misalignment risks in software contexts by separating production data from agent changes.

Currently, mitigating risks in agentic workflows often takes one of two forms:

- Limiting the scope of the agent’s task – Constraining the agent to simple, often single-step subtasks that don't require approval, sometimes avoiding "write" changes entirely (e.g. fetching some context with RAG, summarizing it for the user).

- Pausing agent execution – For multi-step, more complex, or higher-risk tasks, pausing execution and asking permission from the user before executing higher-risk steps (e.g. a trip booking agent that selects flights, hotels, and rental cars could pause after each booking step to get user approval before confirming the next reservation).

The former is not ideal since AI's ability to complete long tasks is increasing (source) – we want to leverage this, not limit it to simple tasks solely for safety reasons.

The latter is also limited in its effectiveness – beyond simply slowing down the execution, repeated requests for users’ approval can lead to “consent fatigue” or “approval exhaustion”, wherein users get tired of having to repeatedly accept or deny changes – they simply click "Accept" each time to dismiss the repeated prompts, undermining the intended purpose.

Ideally, we need a way to review and approve agent outputs before they permanently affect production data – without disrupting their execution and/or limiting their ability to accomplish long-running tasks.

Isolating Agent Changes from Production Data

Notably, software development is one of the few domains where this workflow is already the norm: an agent can make changes locally, which a developer can then inspect, test, and modify before merging into the main codebase. This intermediate step, where agent-generated changes can be verified and iterated on without affecting production, is a major reason agents can be used so effectively in coding contexts.

In non-coding contexts, a similar workflow can be accomplished via Copy-on-Write (CoW) – a widely used concept in computer science where changes are applied to a separate copy rather than the original data, and committed back only when appropriate.

Applied to databases, this approach means storing agent changes in a separate table rather than modifying production data directly. During a session, the agent's changes are ‘merged’ into a view with the original data (it ‘believes’ they have been applied). At the end of a session, these changes can be visualized in a dependency graph and selectively committed by the user.

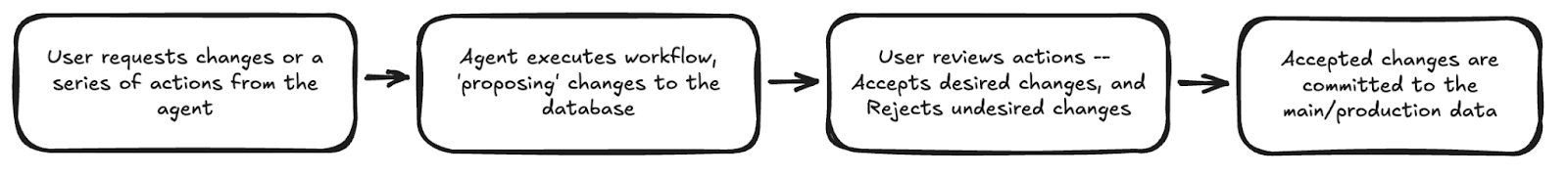

The workflow could look like:

This approach has various benefits:

- Changes can be reviewed at the end of a session, rather than needing to repeatedly ‘accept’ each action as it is executed. This minimizes the direct supervision required while improving the safeguards in place.

- Mistakes are less consequential since the agent can’t write directly to the main/production data. If some changes are good but others aren't, users can cherry-pick operations they wish to keep.

- Misalignment patterns become more visible. When reviewing changes at the end of a session, users can clearly identify where the agent deviated from intended behaviour and adjust the system prompt or agent configuration accordingly to prevent similar issues in future sessions.

- Multiple agents or agent sessions can run simultaneously on isolated copies without interfering with each other.

This kind of operational governance will make human-in-the-loop participation more practical in agentic applications – increasing transparency, reliability, and trust as these systems are deployed more widely.

This article will first describe the CoW mechanism implementation, followed by a worked example of CoW being used in a farm's Inventory Management System to demonstrate how it works in practice.

The following terms will be used to mean:

- Agent session: An ‘agent session’ is a particular sequence of actions/tasks completed by an agent (e.g. checking the inventory of item A → comparing it to the desired inventory → suggesting an order and/or new vendor to purchase additional quantities). Each session has a unique session_id. The length/granularity of each session is determined by the user.

- Agent operation: An ‘agent operation’ is an action taken by the agent. An agent session is composed of multiple agent operations in sequence.

CoW Implementation

The implementation of CoW described in this article assumes an SQL database, but similar mechanisms can be configured in other storage types (noSQL, blob, etc).

Importantly, integrating this implementation into an existing application requires minimal work on the application side – only a few additional parameters to be passed in the datastore transaction. While versioning systems are often technically possible, they typically require extensive modifications to application architecture and workflows, and can introduce significant overhead.

Also, by handling versioning at the database layer, this approach is completely transparent to the agent: the agent 'believes' it is operating on production data, and sees its changes reflected as if they were applied directly.

Database Table Setup

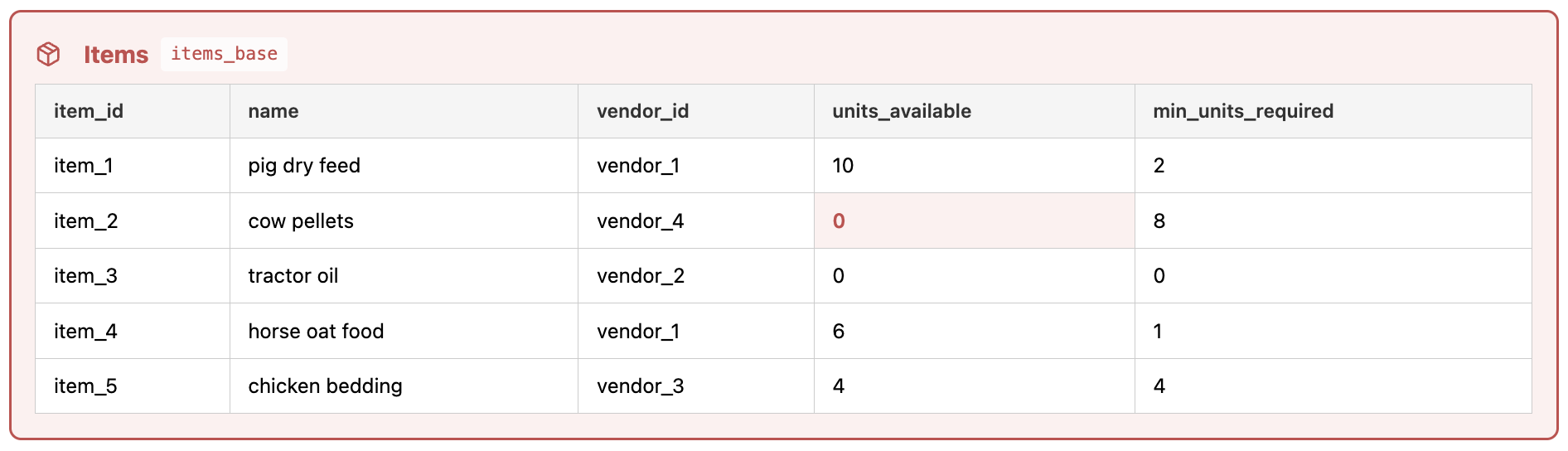

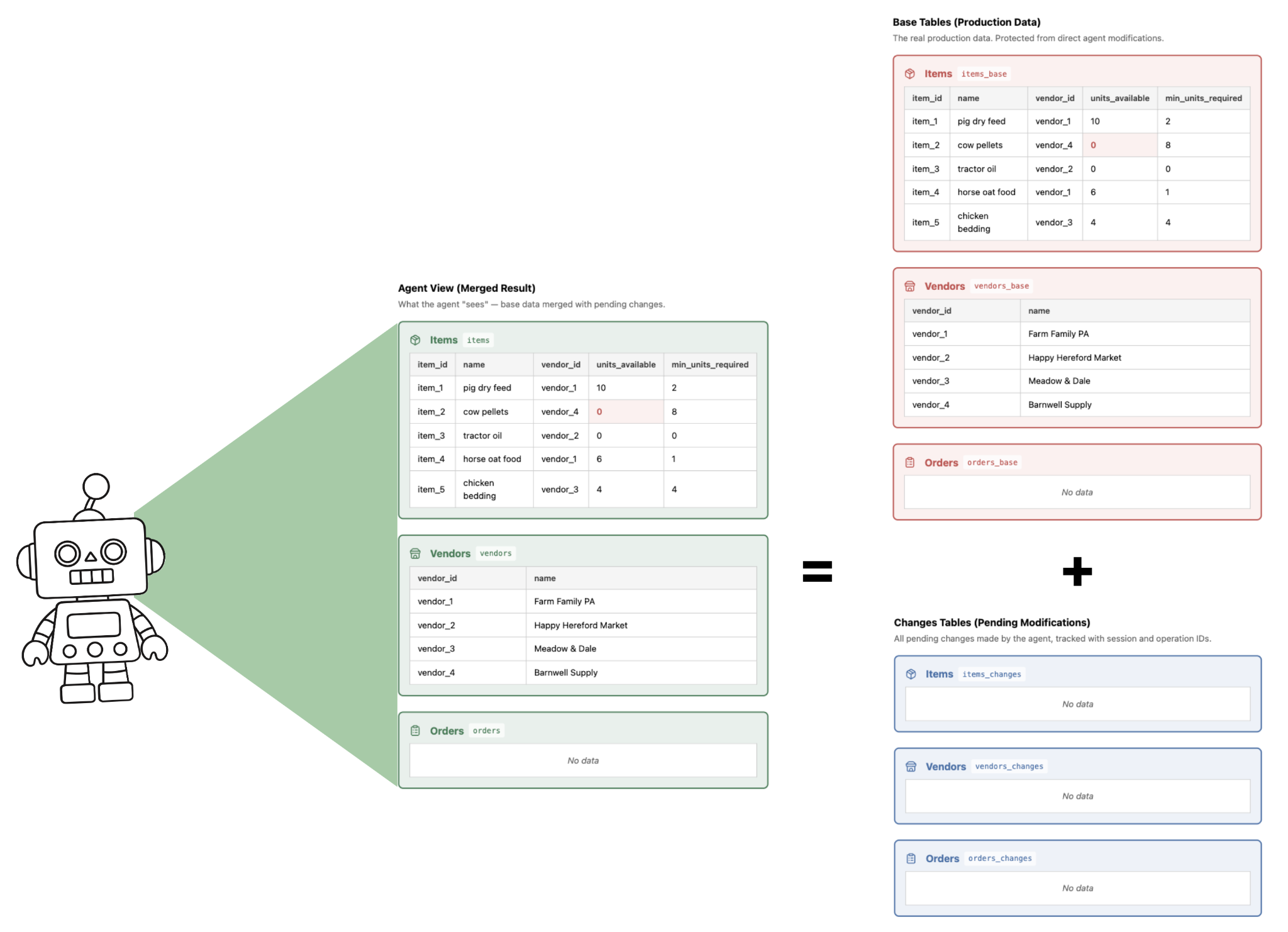

When CoW is enabled, the original database tables are split into a base table, and a changes table.

Base table

Naming convention: <original table name>_base (e.g. items → items_base)

This is the ‘original’ table, and is used as the source of truth in the other parts of the tool. When changes are committed by the user at the end of an agent session, they are merged here from the changes table (see below) to here.

Changes table

Naming convention: <original table name>_changes (e.g. items → items_changes)

This table is added to keep track of changes made through the agent’s operations. When a row of a base table is to be modified/inserted/deleted, the updated version of the row is written to the changes table, and the following columns are appended:

- session_id (uuid): Tracks which agent session associated with the change, allowing changes from separate sessions to be isolated.

- operation_id (uuid): Tracks the agent operation associated with the change.

- _cow_deleted (boolean): Tracks whether the row was deleted by the agent (true if deleted).

- _cow_updated_at (timestamp): Tracks the time at which the operation was done by the agent.

When an agent makes a change, the original row is left as-is in the base table. If the agent makes multiple changes to the same row, there will be multiple corresponding entries in the changes table (with distinct operation_ids).

At the end of an agent session, the user has an option to accept or reject each change and its dependent operations (more on this in CoW Dependencies).

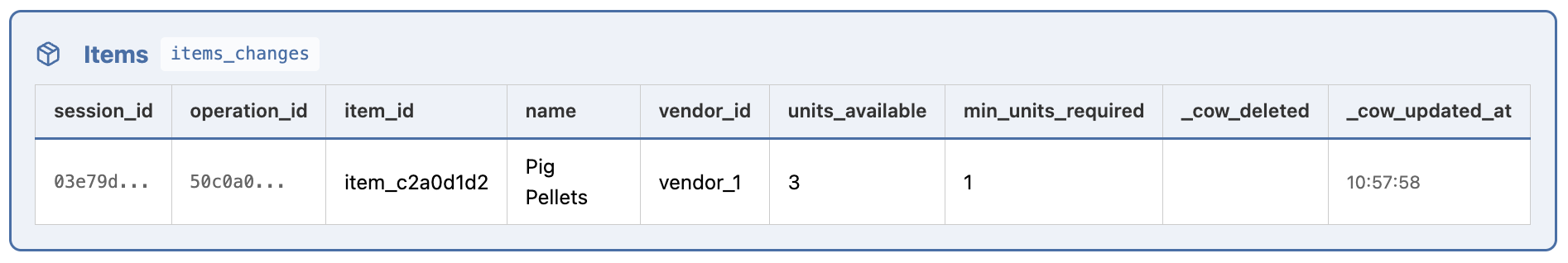

Read Mechanism: View

Naming convention: <original table name> (e.g. items → items)

The agent is not ‘aware’ of the base table, nor the changes table. The agent fetches data using the original table name, and because of the CoW table renaming, this will return the data from the view – which combines data from both tables.

In SQL, a view is a virtual table – it doesn’t store any data, but instead generates table-like results via a query. In this case, the CoW view query:

- Merges each row from the base table with the corresponding row in the changes table,

- Appends any rows from the changes table not present in the base table,

- Filters by the active session_id, and

- Filters deletions (ie. rows where _cow_deleted is true)

This means that rather than reading or writing directly to the original application data, the agent only ever ‘sees’ a view that merges the original data with the changes it has made.

Write Mechanism: INSTEAD OF Triggers

In this section, ‘changes information’ refers to the columns appended to data when it is written to the changes table (i.e. session_id, operation_id, _cow_deleted, _cow_updated_at).

Database triggers are special procedures that automatically execute in response to certain events on a table or view, such as INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE operations. They allow the database to enforce custom logic or side effects whenever data is modified.

CoW uses INSTEAD OF triggers to intercept write operations, redirecting them to the the changes table, with the associated changes information appended.

The triggers are:

- INSERT trigger: When an agent does an INSERT operation, it attempts to write to the original table name, which is now a view. An INSTEAD OF trigger intercepts this → a new row is inserted into the changes table (with changes information appended).

- UPDATE trigger: UPDATE operations ae intercepted via an INSTEAD OF trigger → a new row is inserted into the changes table (the existing primary key value is kept, and changes information appended).

- DELETE trigger: DELETE operations are intercepted via an INSTEAD OF trigger → a new row is inserted into the changes table (all existing column information is kept, and changes information appended).

CoW Dependencies

When a user is committing changes at the end of a session, they can choose which operation(s) they would like to commit.

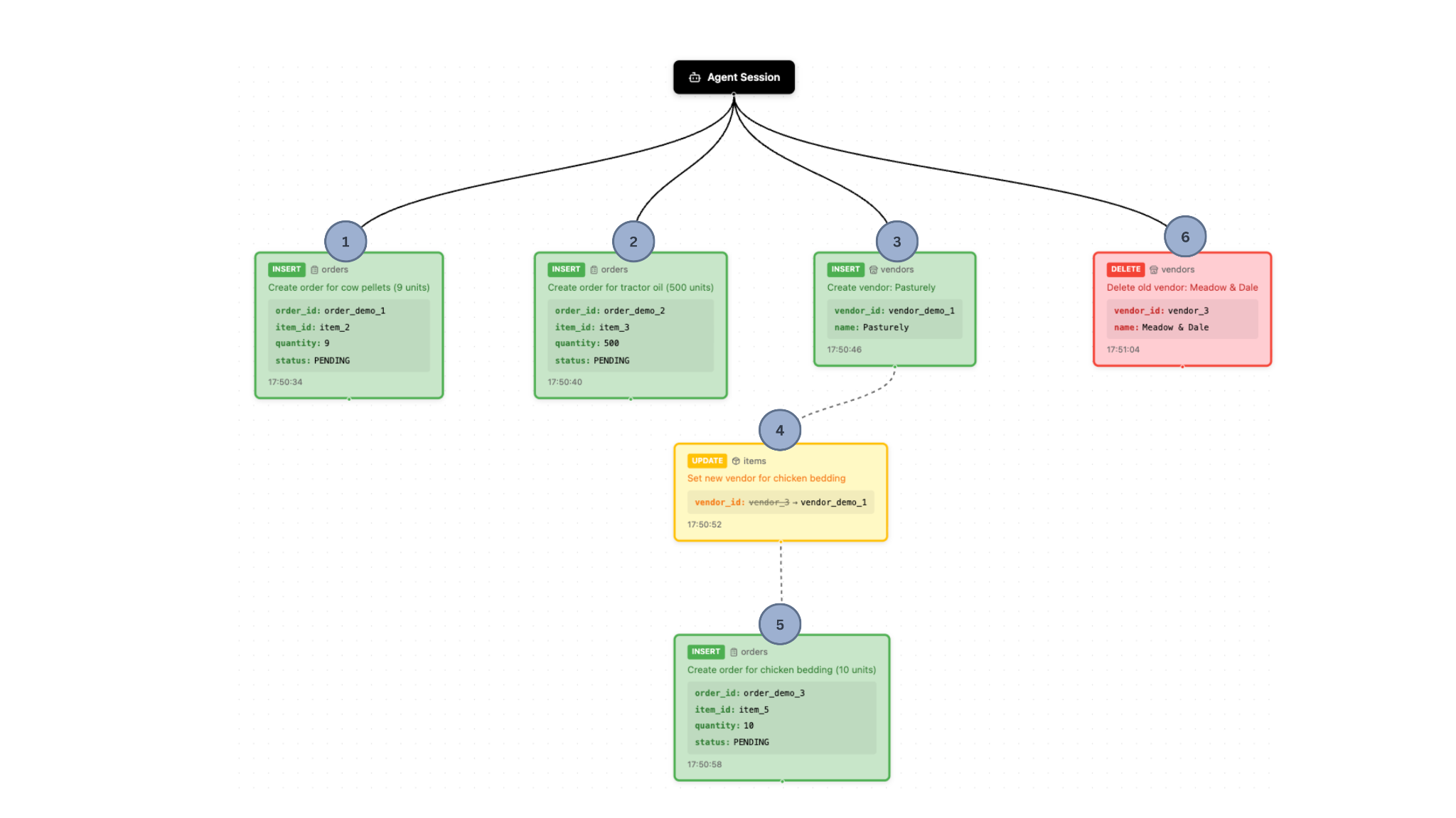

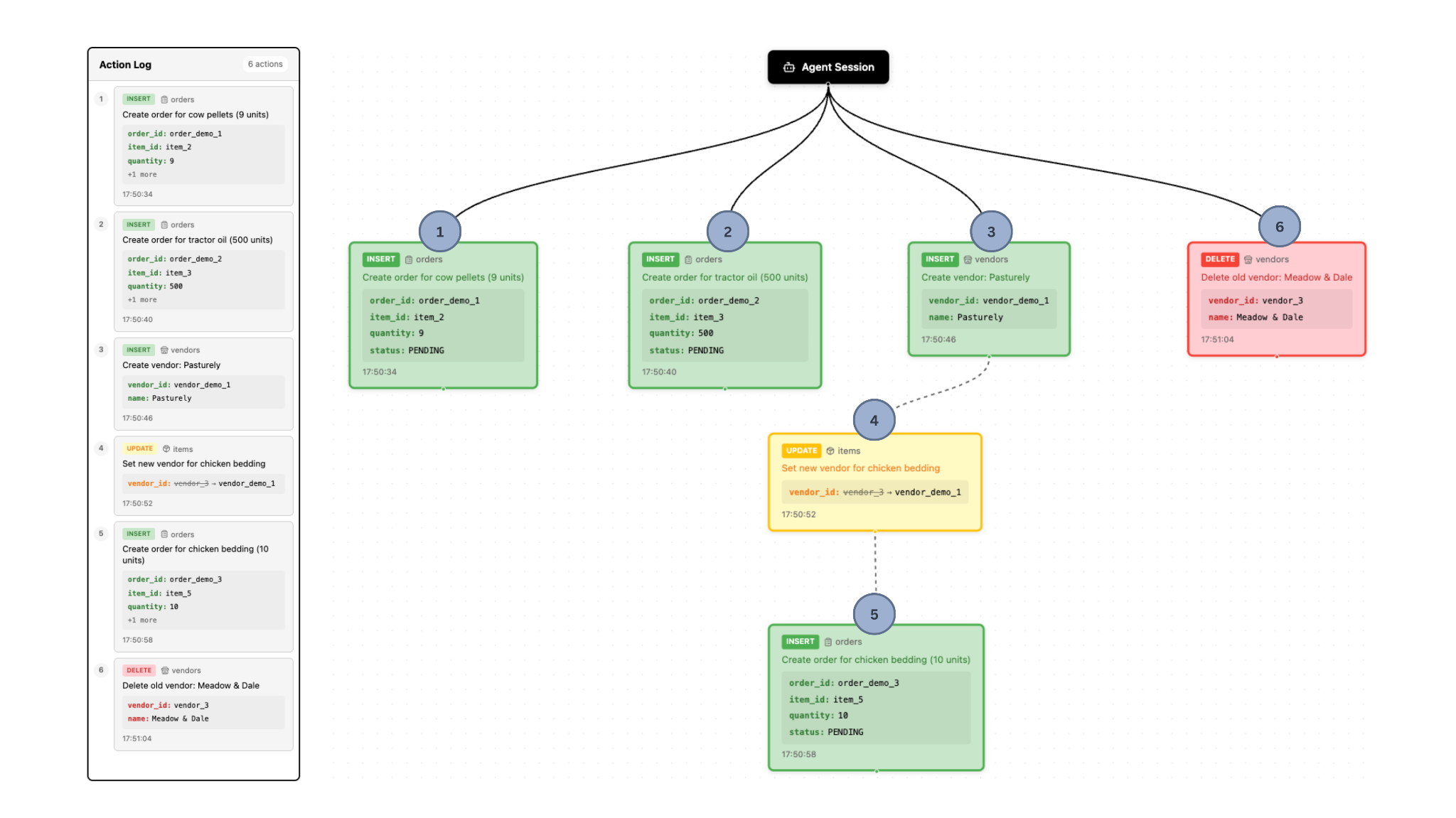

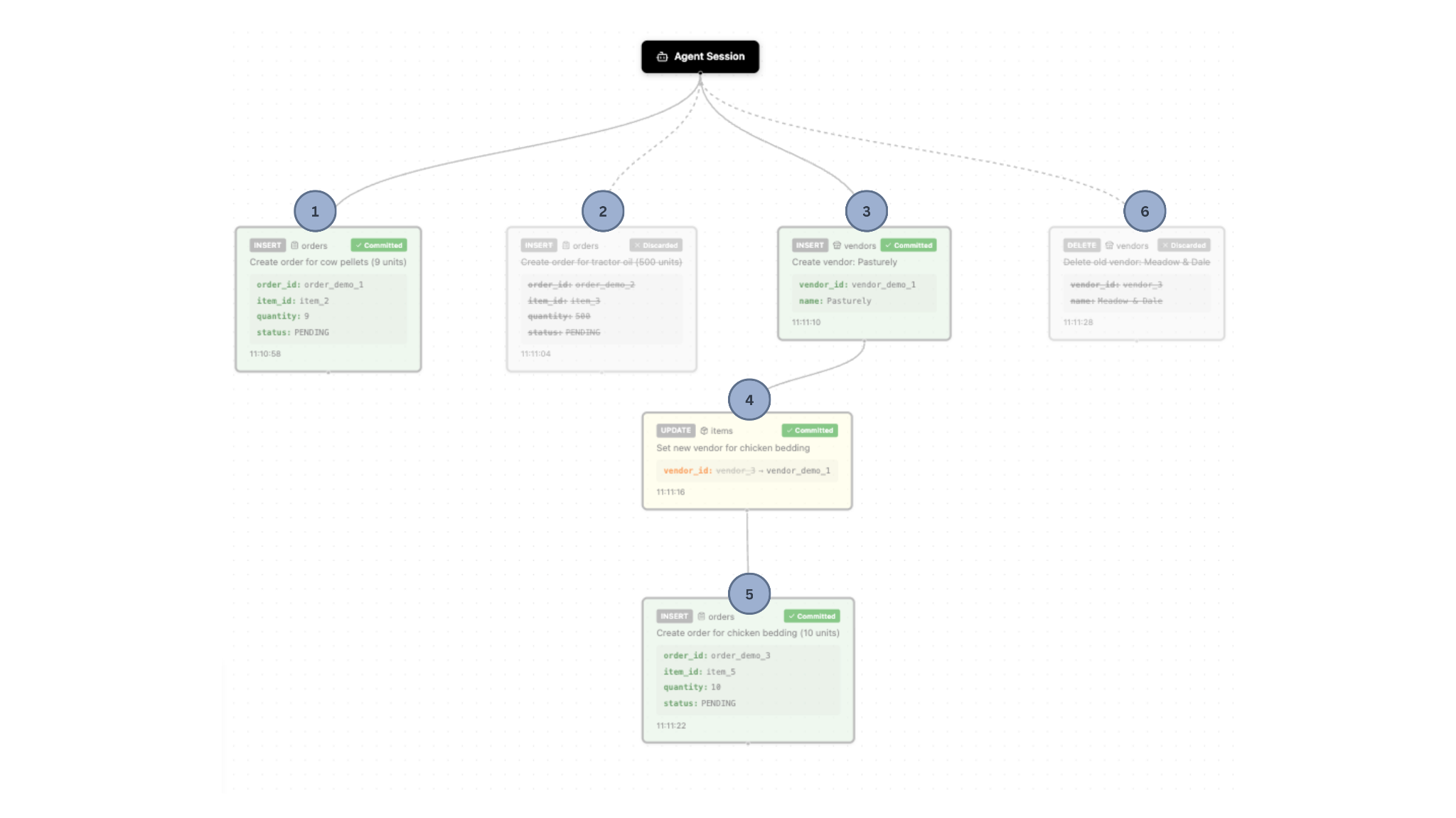

For example, in the image below, the user could select operations 1 and 5 to commit – discarding operations 2 and 6. Doing so will commit the selected operation(s) + all dependent operations: 3 and 4.

It is therefore important to accurately determine dependencies within and between database objects – both within the same table (same-row dependencies) and between tables (cross-table dependencies).

Same-Row Dependencies

If an item is created at 1:00:00 (Operation A), and its name is changed at 1:00:10 (Operation B) – then B is dependent on A.

In general, Operation B is a same-row dependency to Operation A if both touch the same row (same primary key) in the same table, AND A's change happened before B's change.

We can detect this by:

(a) joining each changes table with itself, and

(b) filtering for rows (row_a, row_b) where:

- Primary keys are identical (row_a.primary_key = row_b.primary_key),

- Operation ids are different (row_a.operation_id != row_b.operation_id), and

- One operation was done later than the other (row_a._cow_updated_at < row_b._cow_updated_at)

Pairs of rows that satisfy these conditions are returned as dependency pairs (i.e. row_a, row_b).

Cross-Table Dependencies (Foreign Key relationships)

Imagine we have two tables: Items and Orders. If an Order is created at 1:00:00 (Operation A), and an Item on that order is created/modified at 1:00:10 (Operation B) – then B is dependent on A.

In general, Operation B depends on Operation A if A created/modified a row in one table, B references that row via a foreign key, and A's change happened before B's change.

We can detect this for each table by:

(a) finding all other tables related it (i.e. via its foreign key constraints),

(b) joining the item A’s changes table with the related item B’s changes table, and

(c) filtering for rows (row_table_a, related_row_table_b) where:

- Primary keys are identical (row_table_a.primary_key = related_row_table_b.primary_key),

- Operation ids are different (row_table_a.operation_id != related_row_table_b.operation_id), and

- One operation was done later than the other (row_table_a._cow_updated_at < related_row_table_b._cow_updated_at)

Pairs of rows that satisfy these conditions are returned as dependency pairs (i.e. row_table_a, related_row_table_b).

Committing CoW Changes

At the end of an agent session, the user reviews the changes and decides which operations to accept.

- The user selects which operations they want to commit (ie. merge with the main/production data).

- Dependencies for the selected operations are resolved according to the logic above.

- Operations are sorted in dependency order, and merged with the base tables accordingly:

- Insertions: Rows not already present in the base table are copied from the changes table

- Updates: Rows already existing in the base table are updated with the data from the changes table

- Deletions: Rows marked with _cow_deleted = true in the changes table are deleted from the base table

This logic allows granular control over which changes are accepted by the user and merged with the main/production data, without requiring the user to constantly accept/reject each agent action during its execution.

Worked example

The full interactive demo can be found at: https://agent-cow.com/ (GitHub). The demo system uses a CoW implementation on pg-lite.

Imagine a farm uses an inventory management tool to manage supplies, orders, and vendors. They have integrated an AI agent to monitor inventory levels and suggest changes to the farmer.

Errors in this context (e.g. ordering the wrong items, either in incorrect quantities or from unreliable vendors) could waste resources and cause delays.

They enable CoW to allow the agent to execute sequences of actions autonomously without interruption while enabling sufficient human oversight before the changes are accepted (i.e. before the database is updated and/or orders are placed).

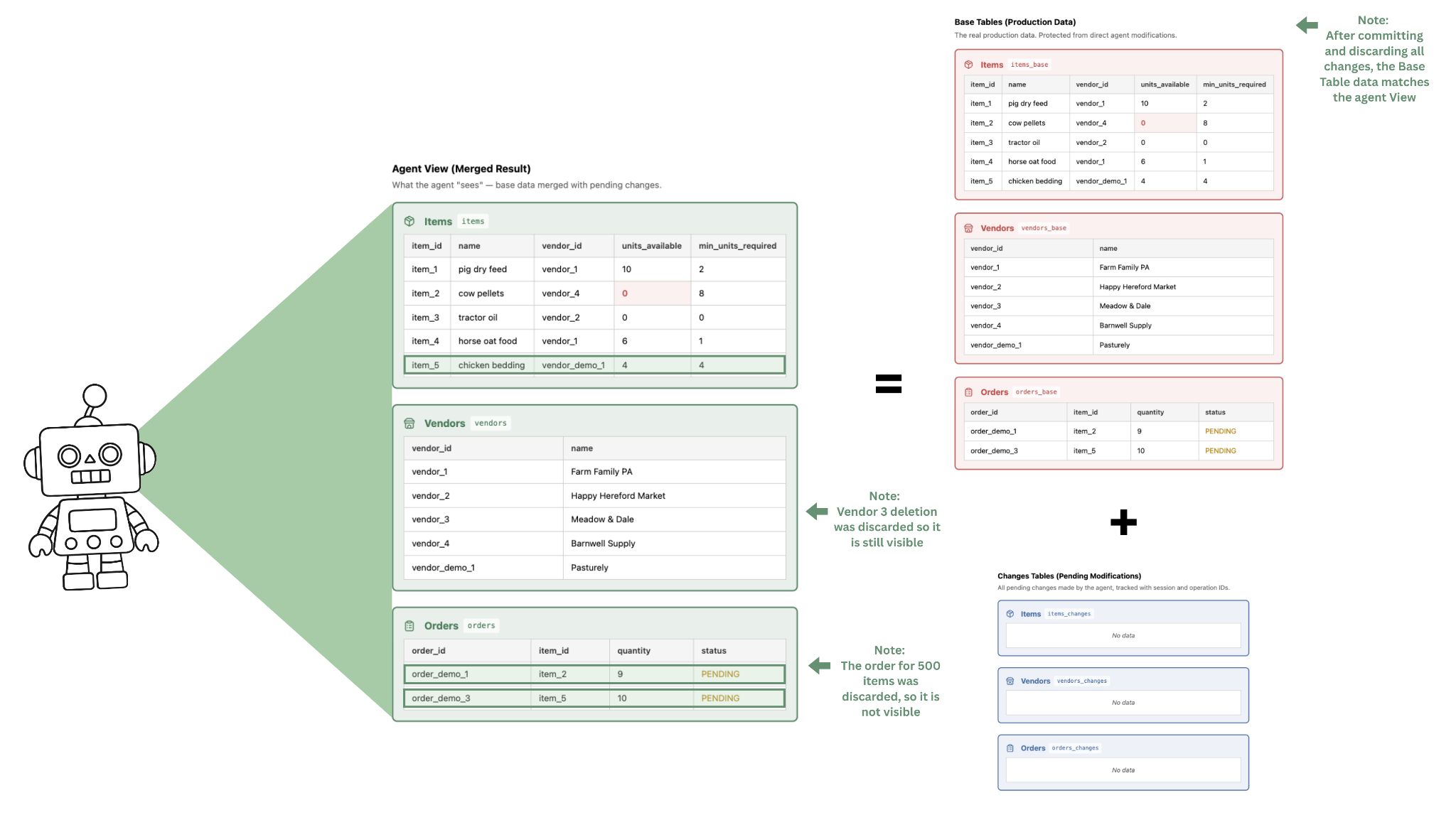

Database Tables

Suppose the farm’s database contains three primary tables:

- Items (tracks each item, its current vendor, and supplies relative to minimum requirements)

- Vendors (tracks vendors and the items they are supplying)

- Orders (tracks item orders and their statuses)

When CoW is enabled, each table is split into two tables (_base, _changes) + a view. The agent can only ‘see’ the view, which combines the base (ie. original data) with the changes it has made.

Now, the farmer prompts the Inventory System Agent:

"Can you please run an inventory check and handle any items that need restocking? Find a new cheaper supplier for the chicken bedding if there's one available."

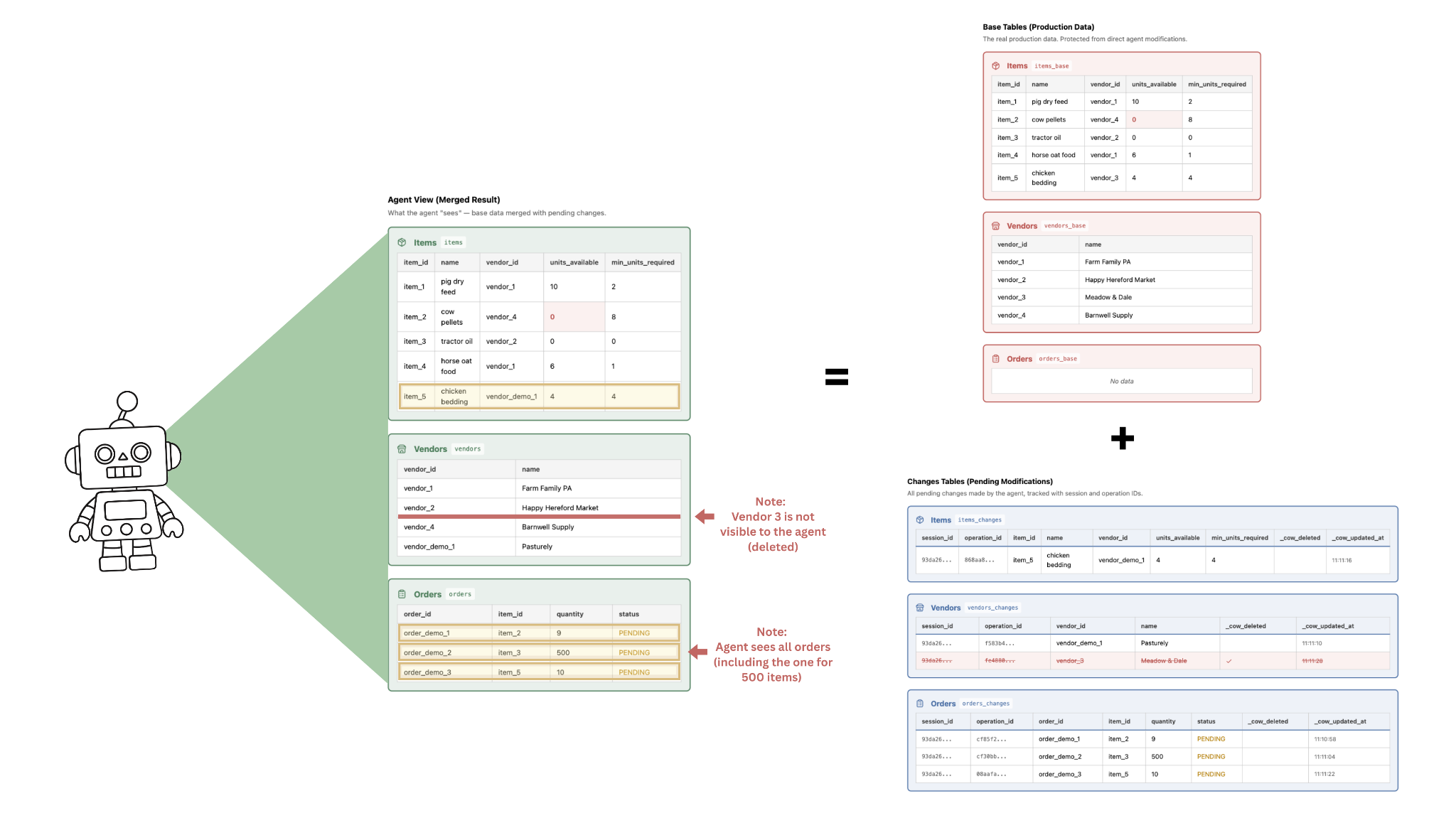

The agent proceeds to execute various tasks in response to the prompt. Figure X shows the state after all agent operations, andFigure X shows the final state of the action log and dependency graph.

Some actions are aligned with the user’s requests. For example:

- The agent discovers that Cow Pellets and Tractor Oil are low on stock, relative to the minimum required values. It then creates entries in the orders table corresponding to these items.

- It successfully finds a new chicken bedding vendor, and creates a corresponding entry in the vendors table.

However, some actions may not be desired. For example:

- Of the orders placed, one is for 5 new units of Cow Pellets, 5 new units of Chicken Bedding, and the other is for 500 new units of Tractor oil. That is far more tractor oil than the farmer has room to store, so she does not want to commit this change to the main/permanent data.

- After finding a new vendor for chicken bedding, the agent deleted the existing one. The farmer does not want this, in case she doesn’t end up liking the new vendor, and wants to re-order from the old one later.

The farmer can then select the operations she would like to accept and reject the ones that are not desired. Figure X shows the dependency graph after committing and discarding, and These actions get committed to the database, so the final state is as in Figure X shows the final state of the database tables.

Key benefits from using CoW:

- The farmer can leave the agent running autonomously for extended periods of time, without needing to directly supervise and/or approve each command. The farmer was able to select which of the changes she wanted to keep (copy over to the main/permanent data), and which she wanted to reject.

- The agent’s mistakes are clear to the farmer – she can adjust the system prompt accordingly in the future. For example, to prevent excessively large orders, she can specify that orders should always be made for 2x the minimum required amount.